Abdominal aortic aneurysms remain a challenging diagnosis for patients. Over the last 18 years, the minimally invasive endovascular approach has developed into a viable alternative to traditional open surgery for the treatment of these abnormal aortic dilatations. Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) is the preferred method of repairing abdominal aneurysms in older and high-risk patients. EVAR has been shown to lead to a decreased early mortality (<30 days) rate and less morbidity compared with open surgical repair.

EVAR of abdominal aneurysms is not without complications, and these differ substantially from those encountered with open surgical repair – whether transabdominal or retroperitoneal. As the procedure and devices have changed, so has the frequency at which these complications occur. The majority of the complications are related to the procedure and are not device-specific. In this review, we will discuss the array of complications according to the timing of occurrence: early (<30 days after the procedure) and late. In addition, we will describe methods to prevent, survey and treat these complications.

Early Complications of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair

Delivery-related Complications

This category includes complications related to arterial access and insertion of the graft up to the aneurysm.

Wound Complications

Wound haematomas can occur with either open or percutaneous arterial access. Lymphoceles, on the other hand, are more of an issue when an open groin access procedure is performed. Careful lymphatic clipping can prevent lymphatic leaks from occurring. The presence of either a haematoma or a lymphocele increases the chance of a wound infection.

Arterial Acccess Complications

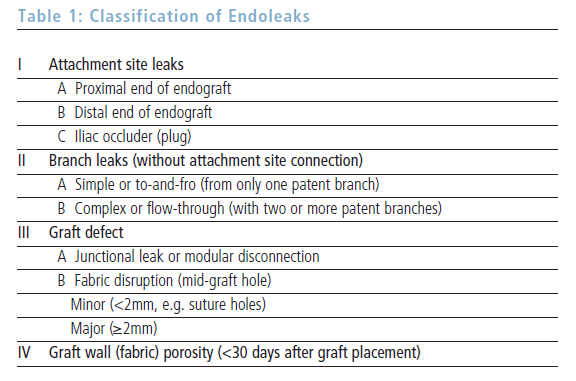

The placement of wires, catheters and sheaths through the common femoral artery is performed under fluoroscopic guidance, but in the setting of an atherosclerotic artery there is still a risk of arterial perforation, rupture and dissection and embolisation of plaque to the viscera or extremities (see Figure 1). If the common femoral artery is severely atherosclerotic, EVAR can be performed via the iliac or brachial artery. In addition to assessing the degree of atherosclerosis, the physician must also pay attention to the size of the artery and degree of tortuosity.1

Careful closure of the arteriotomy either with a percutaneous closure device or by placement of sutures can limit the development of pseudoaneurysms and arterial thrombosis. The development of a pseudoaneurysm is usually treated with ultrasound-guided thrombin injection, but may occasionally require open surgical repair. Arterial thrombosis may require thrombectomy or bypass. Pre-operative documentation of the patient’s distal pulse examination will help to monitor the development of arterial access complications.

Deployment-related Complications

Deployment Failure

This is a rare occurrence, but when it does happen the procedure is abandoned or surgical conversion is undertaken. The most important risk factor for failure to complete the procedure is an aneurysm neck size ≥60mm2.

Renal Ostia Coverage

This complication occurs approximately 2% of the time. Complete coverage of both ostia usually leads to surgical conversion, whereas partial coverage of one ostia can be corrected with the placement of a renal artery stent.3 It is difficult – if not impossible – to move the endograft once it has been deployed.

Hypogastric Artery Embolisation Complications

In certain cases one or both hypogastric arteries must be embolised to permit distal fixation of the endograft into the external iliac artery. The complications of this procedure are related to decreased pelvic arterial flow, with consequences such as buttock claudication.4 The development of gluteal myonecrosis with renal failure is also reported.5

Implant-related Complications

Endoleaks

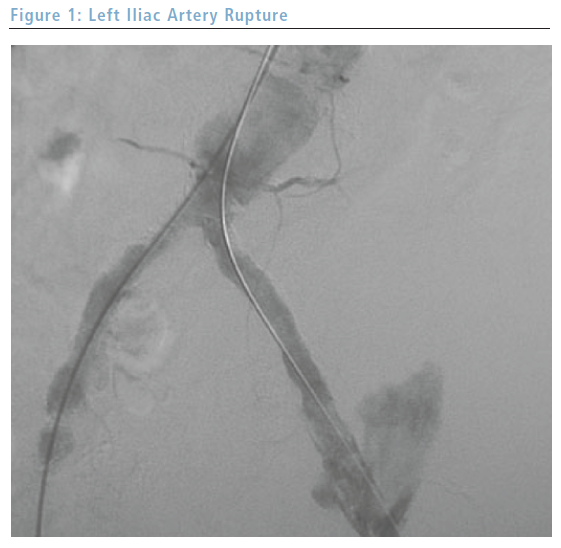

An endoleak is the phenomenon of persistent aneurysm sac perfusion and pressurisation following placement of an endograft. Each type of endoleak (see Table 1) can be noted during the procedure or surveillance period:

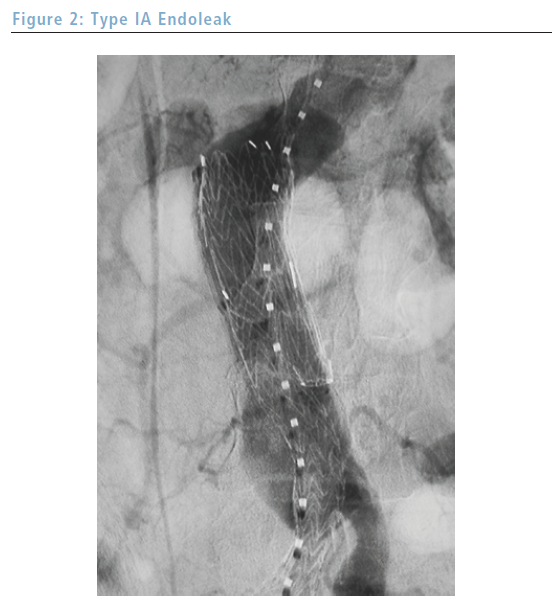

• Type I endoleaks (see Figure 2) are usually noted during the completion angiogram and are associated with an increased rate of aneurysm rupture.6 This association mandates intra-operative correction of type I endoleaks, usually by the placement of additional cuffs; however, open surgical conversion is not unheard of in this situation.

• Type II endoleaks can be seen during the completion angiogram or during the surveillance period and are caused by persistent flow from a patent branch such as the inferior mesenteric artery. The management of this type of endoleak is controversial; one approach is to follow them closely post-operatively and intervene – usually by embolisation – if the sac pressure increases or the aneurysm increases in size. • The design of endografts varies from one manufacturer to the next, but the biggest difference is related to the specifics of the body of the graft: unibody or modular. Unibody devices are formed from one piece, whereas modular devices are composed of a number of pieces. Modular devices can therefore lead to separation of components, resulting in a type III endoleak. This is usually noted on the completion angiogram and can thus be corrected at the time of the procedure with the insertion of stents or cuffs. • The material used to manufacture the device can also have an impact on the development of complications. The two materials employed in different endografts are polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or woven polyester, and they differ by degree of porosity. The more porous PTFE has a higher incidence of the development of type IV endoleaks, although new manufacturing techniques have decreased the porosity. Of note is the fact that these endoleaks usually resolve spontaneously during the post-operative period.

Endograft Limb Occlusion/Thrombosis

This presents with ischaemic symptoms in the extremity and is easily demonstrated on a computed tomography (CT) scan or angiogram. This complication is associated with smaller-diameter endograft limbs and extension to the external iliac artery. In addition, older unsupported grafts had a higher rate of this complication. The management of this complication can vary from thrombolysis and stent placement to open surgical femoral bypass to femoral bypass.1 Thrombectomy is difficult due to the presence of the thin-walled intraluminal graft.

Endograft Limb Kinks

These can lead to ischaemic symptoms and can be seen on a CT scan or angiogram. Risk factors include gender (female), neck angulation, team experience, American Socity of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification and device type.7 This complication can be managed with additional stents.

Systemic Complications

Despite the fact that EVAR results in fewer systemic complications than open surgical repair, these complications still represent the most frequent complication in the post-procedure period.6 Those at increased risk of developing systemic complications are the elderly with poor cardiac function.2 The range of complications includes cardiac and pulmonary dysfunction, renal failure, embolic events and spinal cord ischaemia.

Late Complications of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair

These complications are usually noted on imaging studies for graft surveillance. The common routine is a CT scan at one, six and 12 months following the procedure, and annually thereafter.

Delivery-related Complications

Wound Complications

Lymphoceles and pseudoaneurysms can develop in both the early and late periods; therefore, groin incision examination is an integral part of EVAR surveillance.

Deployment-related Complications

Many findings can be seen on the imaging studies during the follow-up period. The difficulty is knowing if and when one needs to intervene.

Endoleaks

These increase the risk of aneurysm rupture and are the primary reason for such close surveillance following the procedure. Type I and III endoleaks should be intervened upon, usually with cuffs or stents. Type IV endoleaks are usually seen during this period. The management of type II endoleaks is controversial. A common approach is to intervene if there is evidence of sac enlargement; this can be achieved by transarterial embolisation or laparoscopic ligation.8 The one thing that is certain is that the discovery of a new endoleak mandates more frequent follow-up imaging studies.

Endograft Limb Occlusion/Thrombosis

Endograft limb thrombosis and stensosis can occur during this timeframe and are usually treated with another endograft, a bypass or a stent.9

Graft Migration

Distal graft migration is associated with poor proximal fixation.10,11 This complication needs to be treated by re-intervention, as migration can lead to limb occlusion or aneurysm rupture. In addition, proximal migration of the endograft that occludes the renal arteries has been reported.12

Neck Dilatation

The clinical significance of this complication is not known. Smaller necks tend to dilate more than larger necks.13 Distal migration has been associated with neck dilatation, but in only a few studies.14

Sac Expansion

The normal progression of events is that the aneurysm sac decreases in size over time.15 When an increase in sac size is noted, a search for an endoleak is mandatory.

Endotension

This phenomenon is defined as an increase in sac pressure without the presence of an endoleak. This can be measured by sac puncture or by an implantable device. The significance of this complication is not well understood, but some investigators believe that the increased pressure can lead to rupture.

Graft Infection

One of the benefits of the endovascular approach to aneurysm repair is that the incisions are small and the graft is intraluminal, and as such is not exposed to the bowel at any point during the procedure. There are very few reports of endograft infection necessitating graft removal.

Aortoduodenal Fistula

This complication is thankfully rare.9 Its management includes endoscopy, graft removal, aortic debridement and in situ or extra-anatomical bypass.

Implant-related Complications

Hook fractures, modular component separation and fabric erosion can all occur and be seen during the surveillance period. Hook fractures have been associated with distal graft migration. The other two issues are usually treated with the placement of an additional stent or cuff.

Systemic Complications

Very few systemic complications occur during the late period. The surveillance regimen of serial CT scans with intravenous (IV) contrast place those patients with pre-existing renal failure at greater risk of late renal failure.

Conclusion

EVAR has benefited many patients who would not have fared so well with open surgical repair. It is important to remember that this procedure has many complications that must be recognised because many of them are easily treated. Careful pre-operative assessment of the patient and the aneurysm can help to guide the choice of arterial access routes and endograft type, and attention to proximal and distal fixation and seal can help to limit the development of the serious type I and III endoleaks. Ôûá